News Story

Hartzell Selected for MMX Science Team

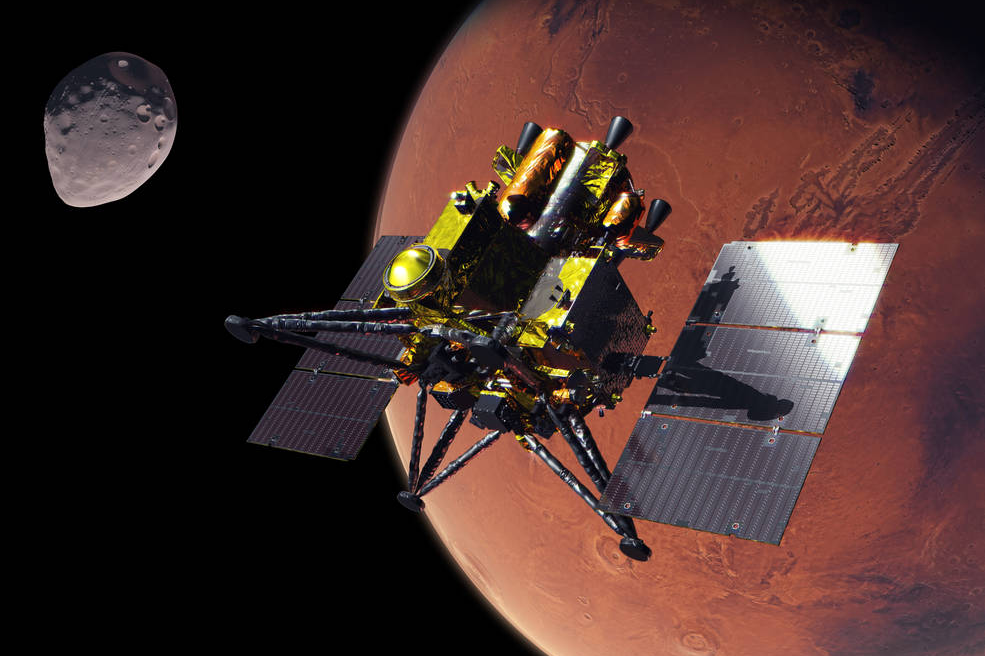

Christine Hartzell, associate professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Maryland (UMD) and director of the Planetary Surfaces and Spacecraft Lab, has been selected to join the Science Working Team for the Martian Moons eXplorer Mission, which is sending a spacecraft to Phobos—one of two moons that orbit Mars—with a launch planned in 2024.

Hartzell is among ten U.S. scientists tapped by NASA for the mission, led by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) in partnership with France’s National Center for Space Studies (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR).

The MMX spacecraft will land on Phobos twice to collect samples. It will also deploy a rover engineered by CNES and DLR—the first such vehicle ever to travel on the surface of a Martian moon, and in an environment of such low gravity. Rover deployment on Phobos is expected in 2027, with the craft then spending 100 days exploring the moon.

The findings, scientists hope, will reveal specifics that can’t be gleaned from remote data, thus providing insights that could help explain Phobos’s origins.

“We know the surface of Phobos is coated with loose rock and dust we call regolith,” Hartzell said. “But does it behave more like dry sand, or more like baking flour, which is very clumpy? Clumps are formed due to strong cohesive bonds between the dust particles and we see them all the time on Earth, but we have never specifically looked for them on another planetary body. The presence or absence of clumps will be an indication of the material properties of regolith, which will inform our understanding of the surface of small moons and asteroids, and potentially inform the design of the next spacecraft to explore these bodies.”

As an MMX participating scientist, Hartzell will use her analytical expertise, as well as modeling tools developed at her lab, to arrive at findings based on data sent back by the rover.

“The rover is equipped with cameras that look at the wheels as well as its navigational cameras, so we’ll be able to watch as the wheel drives over a rock and see if the rock is coherent or if it crumbles,” she said. A rock that crumbles is likely just a clump of smaller particles, like you see in baking flour.

The findings can then be compared to analytical models, which predict that clumps should be present and also estimate the size of those clumps.

Scientists may also be able to extrapolate the findings to other bodies in the solar system in ways that have implications for space exploration and travel, Hartzell said.

“If we observe clumps on Phobos in this mission, it would be an indication that such clumps also occur on other bodies in the solar system,” she said. “Right now, we look at remote images of what seem to be rocks on asteroids or comets, but we’re not really sure what they are. If it turns out they are just clumps that crumble and fall apart, this could lead us to rethink how we design the wheels, other equipment, and operational procedures for other missions to other bodies.”

A member of the UMD aerospace engineering faculty since 2014, Hartzell is also a scientist on the NASA SIMPLEx Janus Mission, which will send a pair of space vehicles to investigate two pairs of binary asteroids, as well as the OSIRIS-REx mission, which focuses on the study of near-earth asteroids. The OSIRIS-REx spacecraft arrived at its first destination, Bennu, in 2018, collecting samples and imagery that have transformed scientific understanding of the asteroid.

Published April 23, 2023